The cephalhematoma (head hematoma) is a collection of blood on the head of a newborn. It occurs mainly in difficult births and a narrow birth canal. The cephalhematoma is palpable after birth on the head of the newborn, usually as a flaccid, later as a bulging tumor. It usually goes away on its own within a few weeks. Read all about cephalhematoma here!

ICD codes for cephalhematoma: P12

Quick overview

- Course of the disease and prognosis: Usually very good, disappears after a few weeks to months; sometimes increased neonatal jaundice, very rarely complications.

- Symptoms: doughy-soft, later firm-elastic swelling on the newborn’s head.

- Causes and risk factors: Shear forces acting on the child’s head during birth, increased risk with aids such as forceps or suction cups.

- Examinations and diagnosis: Visible and palpable swelling on the head, ultrasound examination to rule out further head injuries.

- Treatment: Usually no treatment required.

What is a cephalhematoma?

The word cephalhematoma describes a collection of blood on the head of a newborn. “Kephal” comes from the Greek and means “belonging to the head”. Doctors call a hematoma a bruise or a compact accumulation of blood in the tissue.

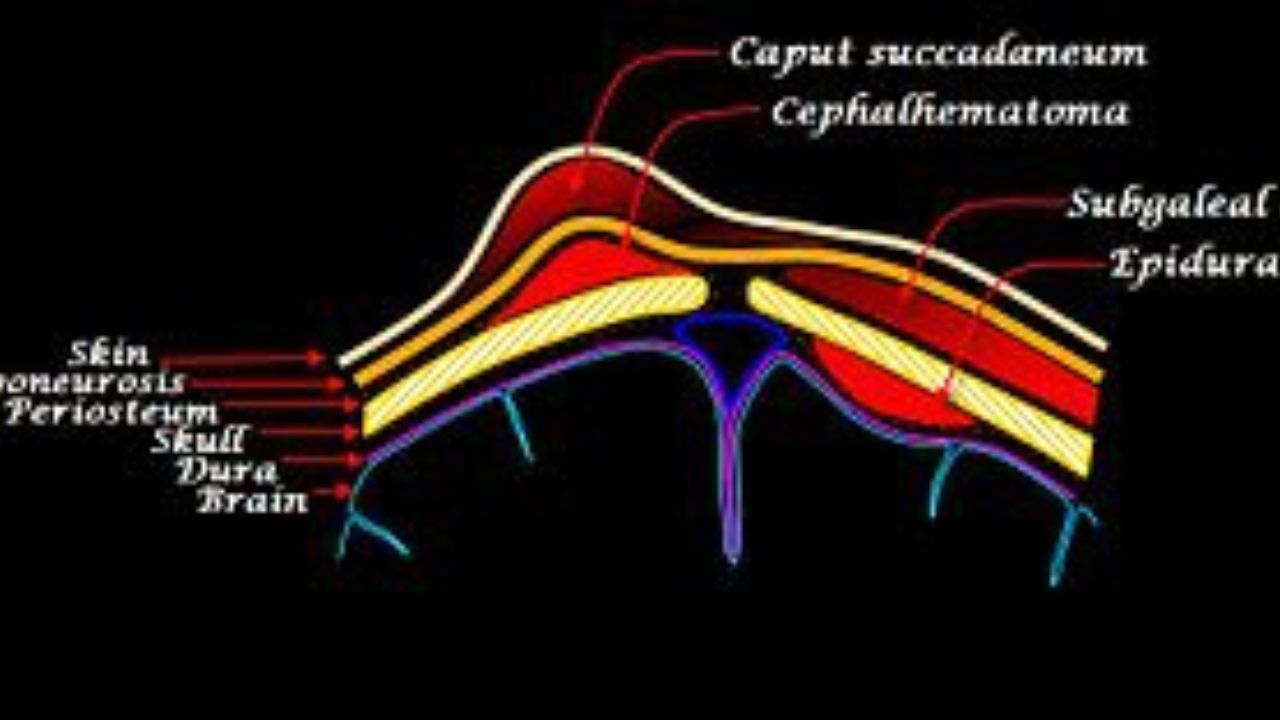

The cephalhematoma forms during natural birth by rupturing small blood vessels between the outer bone of the skull and its periosteum. This happens, for example, when the child’s head is exposed to large forces in the birth canal.

The structure of the skull in the newborn

The newborn’s skull is still soft and malleable. The so-called scalp sits on the outside. These include the scalp with its hair and the subcutaneous fatty tissue as well as the hood-like muscle-tendon plate (galea aponeurotica).

Underneath lies the skull bone, which consists of several parts. These are not yet firmly attached to each other in the newborn. The inside and outside of the skull bones are covered by the so-called periosteum. It protects and nourishes the bone.

The cephalhematoma forms between the periosteum and the bone. It is bounded by the edges of the skull bone. This makes it easy to distinguish it from another typical head swelling in newborns, the so-called birth tumor.

In contrast to a cephalhematoma, a birth tumor exceeds the boundaries of the individual cranial bones and the periosteum continues to lie against the bone.

Cephalic hematoma: Occurrence

According to medical literature, a cephalhematoma occurs in one to two out of 100 births. It is possible that the skull bone is incompletely fractured (cracked) at the same time. Doctors call this “infraction”.

Especially forceps births or suction cup births (vacuum extractions) are associated with the development of a cephalhematoma. The doctor puts either so-called forceps spoons or a suction cup on the child’s head to help him into the world.

Cephalic hematoma: are there late effects?

The overall prognosis for cephalhematoma is very good. In the first few days after birth, it often increases in size and changes in texture. The blood that initially coagulated in the hematoma liquefies over time as it breaks down. The hematoma eventually disappears within a few weeks to months.

In some cases, however, the edges of the cephalic hematoma calcify along the cranial sutures and remain palpable as a bony prominence for a long time. This bony wall later recedes in the course of bone development. Rarely does a cephalhematoma become infected. This situation is potentially life threatening.

What are the symptoms of cephalhematoma?

A cephalhematoma often becomes noticeable immediately after birth. Typical is initially a doughy-soft, later firm-elastic, mostly one-sided swelling on the head of the newborn. It occurs most frequently on one of the two parietal bones (os parietale), which forms the top and back of the bony skull.

The cephalhematoma has a hemispherical shape and sometimes reaches the size of a hen’s egg. The periosteum is sensitive to pain. As a result, newborns with a cephalhematoma may be more restless and cry more, especially when there is external pressure on the cephalhematoma.

If a cephalhematoma does not regress or if it is very large, this is considered a possible indication of impaired blood clotting in the newborn. In some cases, newborn jaundice (neonatal jaundice) worsens due to the reduction of the cephalhematoma.

What are the causes and risk factors of cephalhematoma?

The reason for the development of a cephalhematoma are shear forces acting on the newborn’s head in the narrowness of the birth canal. Due to these forces, the soft tissues of the head are displaced and the periosteum is sheared off the bone.

Vessels under the periosteum tear and begin to bleed. The periosteum is well supplied with blood, so the bleeding is sometimes relatively heavy. If the space between the less stretchable periosteum and the bone is full (sign: bulging elastic swelling), the bleeding stops.

Cephalic hematoma: risk factors

The main risk factors for the development of a cephalhematoma are suction cup delivery and forceps delivery. However, a particularly rapid passage of the child’s head through the mother’s pelvis or a very narrow birth canal also cause shear forces that sometimes lead to a cephalic hematoma.

Another risk factor is the so-called occipital position or parietal position. The child’s head does not lie forehead first in the mother’s pelvic entrance, making entry into the birth canal more difficult.

How do you recognize a cephalhematoma?

The midwife or pediatrician often discovers the cephalhematoma shortly after birth. Sometimes the very common, so-called birth swelling on the head of the newborn superimposes the cephalhematoma. Only when it recedes after a few days can the cephalhematoma be recognized.

If you have noticed the cephalhematoma yourself, your midwife or pediatrician are also your contacts. Possible questions in the introductory conversation (medical history) are, for example, the following:

- When did you notice the swelling?

- Has the swelling changed in size or texture?

- How did your child’s birth go? Were aids such as suction cups or forceps used?

- Is a head injury possible after childbirth?

Cephalic Hematoma: Physical Examination

During the examination, the doctor checks whether the sutures between the skull bones limit the tumor or whether the swelling extends beyond it. The former would be a typical sign of cephalhematoma. He also checks the consistency of the swelling.

A cephalic hematoma rarely superimposes an injury to the cranial bone. In order to exclude this, an ultrasound examination is usually carried out on the newborn’s head.

The pediatrician may examine the child for any neurological (= nervous system related) abnormalities. Among other things, it shines in your child’s eyes (testing the pupil’s light reaction) and checks whether your child reacts to acoustic stimuli (noises), for example.

Cephalic Hematoma: Similar diseases

Your pediatrician must rule out other diseases for a reliable diagnosis of “cephalhematoma”. This includes:

- Galea hematoma (bleeding under the scalp)

- Edema of the scalp (caput succedaneum, also “birth swelling”), a build-up of fluid caused by blood congestion in the scalp during childbirth

- Encephalocele, leakage of brain tissue through the not yet closed skull due to a malformation

- Fall or other external force

How is a cephalhematoma treated?

The cephalhematoma usually does not require any special treatment. It will go away on its own within a few weeks. A puncture to suck out the hematoma should be avoided: it poses a risk of infection for the newborn.

Vitamin K is recommended for children with cephalhematoma to prevent further growth of the bruise. Vitamin K plays a crucial role in blood clotting. However, all newborns, regardless of an existing cephalhematoma, receive vitamin K as a precaution.

If there is an open wound on the scalp in addition to the cephalhematoma, a sterile bandage is required to prevent infection of the hematoma. With large hematomas, doctors monitor the level of bilirubin in the blood.

Newborns break down more red blood cells immediately after birth. This produces bilirubin, which the liver has to convert before the body eliminates it. If the concentration of bilirubin is very high, it has a damaging effect on the newborn’s nervous system (kernicterus).

Sometimes babies with a cephalhematoma have more bilirubin levels because the liver doesn’t break it down fast enough. A special light therapy (blue light phototherapy) helps to lower the bilirubin concentration.