Pancreatic cancer is a tumor of the pancreas, an organ that is located behind the stomach, in the abdomen. Pancreatic cancer usually does not cause symptoms until the tumor has spread. It is slightly more common in men and affects African-Americans at higher rates.

Your doctor may order blood, urine, or tissue tests to look for certain substances that could indicate cancer. Other tests may include an MRI of the body, a CT scan of the body, MRCP, endoscopic ultrasound, or PET/CT to help determine if you have cancer and if it has spread. A biopsy may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis of cancer. Treatment options depend on whether the disease has spread and include surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy, or a combination of these.

What is pancreatic cancer?

Pancreatic cancer starts in the pancreas, an organ that is located deep in the abdomen behind the stomach. The pancreas secretes hormones called insulin and glucagon to help the body process sugar. It also produces enzymes to help the body digest fats, carbohydrates, and proteins.

Pancreatic cancer occurs when abnormal cells grow out of control and develop into a tumor. Most tumors of the pancreas begin in the cells that line the ducts of the pancreas and are known as adenocarcinomas. Tumors of the pancreas that begin in cells that produce hormones are called pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors or pancreatic islet cell tumors.

Pancreatic cancers affect approximately 46,000 Americans each year, making it the 12th most common type of cancer in the United States. Risk factors for the disease include smoking, being overweight, diabetes, older age, having tested positive for the BRCA2 gene, and having a history of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) or a family history of breast cancer. pancreas. Pancreatic cancer is slightly more common in men than women and affects African-Americans at higher rates.

Patients usually do not have symptoms until the tumor has spread to nearby organs. Eight out of 10 patients are diagnosed after the cancer has spread beyond the pancreas. As a result, pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States.how pancreatic cancer is diagnosed and evaluated?

How pancreatic cancer is diagnosed?

When a person has signs and symptoms that could be caused by pancreatic cancer, certain exams and tests will be done to find the cause. If cancer is found, more tests will be done to help determine the extent (stage) of the cancer.

Medical history and medical examination

Your doctor will ask about your medical history and will want to learn more about your symptoms. He may ask you about possible risk factors, including smoking and family history.

Your doctor will also check you for signs of pancreatic cancer or other health problems. Pancreatic cancers can sometimes cause growth of the liver or gallbladder that the doctor can feel during the exam. Your skin and the whites of your eyes will also be checked to see if you have jaundice (a yellowish color).

If the test results are abnormal, your doctor will likely order tests to help find the problem. You may also be asked to see a gastroenterologist (a doctor who treats diseases of the digestive system) for further testing and treatment.

Imaging studies

Imaging tests use sound waves, x-rays, magnetic fields, or radioactive substances to make pictures of the inside of the body. Imaging tests may be done for a variety of reasons both before and after a diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. These reasons include:

• To find suspicious areas that could be cancerous.

• Know how far the cancer has spread.

• Help determine if treatment is effective.

• Identify signs of cancer coming back after treatment.

Computed tomography

Computed tomography (CT) scans produce detailed cross-sectional images of your body. CT is often used to diagnose pancreatic cancer because it can show the pancreas quite clearly. Also, this test can help show whether the cancer has spread to organs near the pancreas, as well as to lymph nodes and distant organs. A CT scan can help determine if surgery may be a good treatment option.

If your doctor thinks you have pancreatic cancer, he or she may order a type of CT scan, known as multiphase CT or pancreatic protocol CT. In this study, different sets of CT scans are taken over several minutes after you receive an intravenous (IV) contrast injection.

CT- guided needle biopsy: CT can also be used to guide the biopsy needle into an area of suspected pancreatic tumor. But if a needle biopsy is needed, most doctors prefer to use endoscopic ultrasound (described later) to guide the needle into the tumor.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays to create detailed images of parts of your body. Most doctors prefer to examine the pancreas with a CT scan, but an MRI can also be done.

In addition, special types of MRI may be used in people who may have pancreatic cancer or are at increased risk of pancreatic cancer:

• MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) can be used to look at the bile and pancreatic ducts. It is described later in the section on cholangiopancreatography.

• MR angiography (MRA) is used to look at blood vessels. It is discussed later in the section on angiography.

Ultrasound

In ultrasound studies, sound waves are used to produce images of organs, such as the pancreas. The two most commonly used types for pancreatic cancer are:

• Abdominal ultrasound: If it’s not clear what might be causing a person’s abdominal symptoms, this test may be the first to be done because it’s easy to do and doesn’t expose the patient to radiation. However, the CT scan is usually more helpful if the signs and symptoms indicate that they are more likely to be caused by pancreatic cancer.

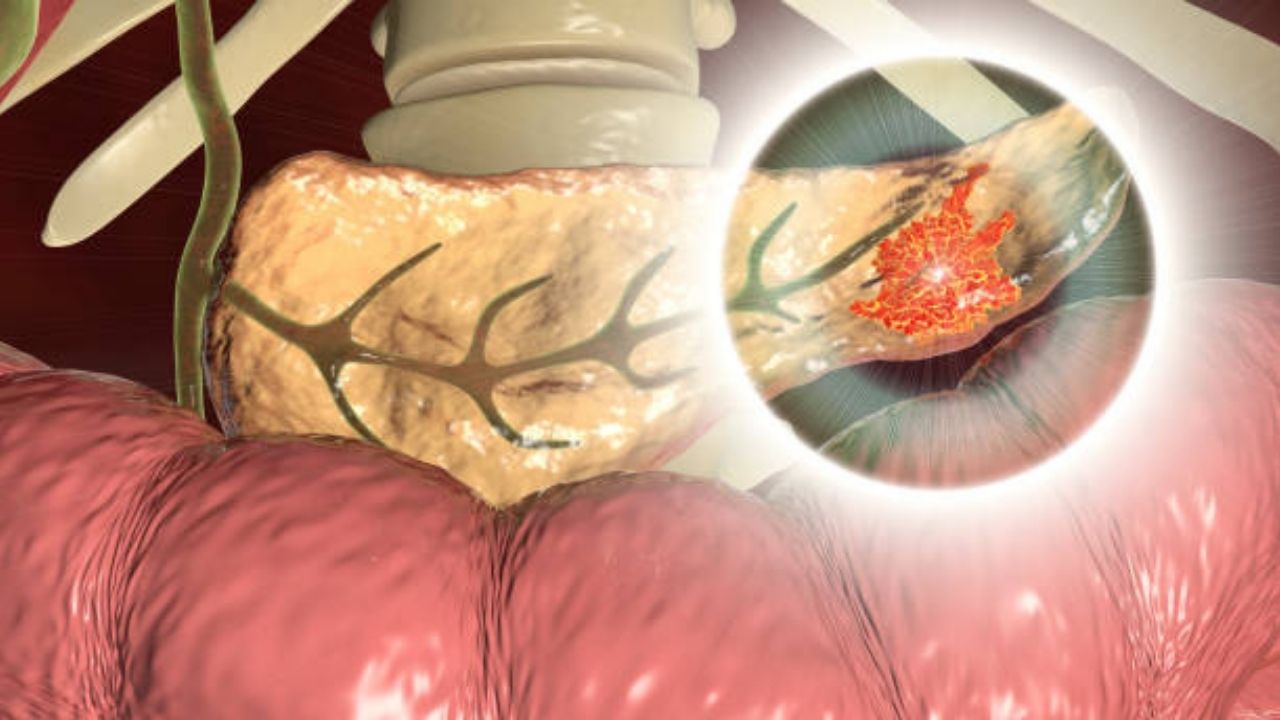

• Endoscopic ultrasound: This test is more accurate than abdominal ultrasound and can be very helpful in diagnosing pancreatic cancer. This test is done with a small ultrasound probe on the end of an endoscope (a thin, flexible tube that doctors use to look inside the digestive tract and to biopsy samples of a tumor).

Cholangiopancreatography

This imaging test allows the pancreatic ducts and bile ducts to be viewed to determine if they are narrowed, blocked, or dilated. These tests can help show if a person might have a pancreatic tumor that is blocking a duct. It can also be used to help plan surgery. This study can be done in different ways, each of which has advantages and disadvantages.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): For this procedure, an endoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a video camera on the end) is inserted into the throat and passed down the esophagus and stomach until it reaches the beginning of the small intestine. The doctor can look through the endoscope to find the ampulla of Vater (where the common bile duct empties into the small intestine).

X-rays taken at this time may show a narrowing or blockage of these ducts that could be caused by pancreatic cancer. The doctor doing this test may put a small brush through the tube to collect cells for biopsy or put a stent (small tube or stent) into a bile or pancreatic duct to keep it open if a nearby tumor presses on it.

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This study is a noninvasive way to examine the pancreas and bile ducts using the same type of machine used for conventional MRIs. Unlike ERCP, it does not require an infusion of contrast material. Because this study is noninvasive, doctors often use MRCP when they only want to look at the bile and pancreatic ducts. However, this test cannot be used to biopsy samples of tumors or to stent ducts.

Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiopancreatography (PTC): In this procedure, the doctor puts a thin, hollow needle through the skin of the abdomen and into a bile duct inside the liver. Contrast dye is then injected through the needle, and x-rays are taken as the dye passes through the bile and pancreatic ducts. Like ERCP, this method can also be used to take fluid or tissue samples or to place a stent in a duct to help keep it open. Because it is a more invasive procedure (and can cause more pain), PTC is not usually used unless ERCP has already been tried or ERCP cannot be done for some reason.

Positron emission tomography

To perform a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, a slightly radioactive form of sugar is injected that accumulates mainly in cancer cells. A special camera is then used to create a picture of the areas of radioactivity in the body.

This test is sometimes used to look for the spread of exocrine pancreatic cancers.

PET/CT study: Special machines can do a PET and CT scan at the same time. This allows the doctor to compare areas of higher radioactivity on PET with the more detailed appearance of that area on CT. This test can help determine the stage (extent) of the cancer. It can be especially helpful in finding cancer that has spread beyond the pancreas and could not be removed by surgery.

Angiography

Angiography is an x-ray study used to examine the blood vessels. A small amount of contrast dye is injected into an artery to outline blood vessels, and x-rays are taken.

An angiogram can show if the blood flow to a particular area is blocked by a tumor. It may also show abnormal blood vessels (feeding the cancer) in the area. This test can be helpful in finding out if pancreatic cancer has grown outside the walls of certain blood vessels. It is mainly used to help surgeons decide if the cancer can be completely removed without damaging vital blood vessels, and it can also help them plan the operation.

X-ray angiography can cause discomfort because the doctor has to insert a small catheter into the artery leading to the pancreas. The catheter is usually inserted into an artery in the groin and guided to the pancreas. A local anesthetic is usually given to numb the area before the catheter is inserted. After the catheter is inserted, the dye is injected to outline all the vessels while x-rays are taken.

Also, angiography can be done with a CT scanner (CT angiography) or an MRI scanner (MR angiography). These techniques are used more often now because they can provide the same information without the need for a catheter in the artery. You may still need an IV line so the contrast dye can be injected into your bloodstream during the imaging test.

Blood test

Several types of blood tests may be used that may be helpful in diagnosing pancreatic cancer or, if found, in determining treatment options.

Liver function tests: Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) is often one of the first signs of pancreatic cancer. Doctors often order blood tests to assess liver function in people with jaundice to help determine its cause. Certain blood tests can check the levels of different types of bilirubin (a chemical produced by the liver) and can help determine if a patient’s jaundice is caused by liver disease or an obstruction of bile flow (either by a gallstone, a tumor, or some other disease).

Tumor markers: Tumor markers are substances that can sometimes be found in the blood when a person has cancer. Tumor markers that may be useful in pancreatic cancer are:

- CA 19-9

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) which is not used as often as CA 19-9

None of these tumor marker tests is accurate enough to tell for sure if someone has pancreatic cancer. Levels of these tumor markers are not elevated in everyone with pancreatic cancer, and some people who do not have pancreatic cancer may have high levels of these markers for other reasons. Still, these tests can sometimes be helpful, along with other tests, in determining if a person has cancer.

In people known to have pancreatic cancer who have high levels of CA19-9 or CEA, these levels may be measured over time to help learn how well treatment is working. If the entire cancer is removed, these tests may also be done to look for signs that the cancer may be coming back.

Other blood tests: Other tests, such as a complete blood count (CBC) or blood chemistry tests , can help assess a person’s overall health (such as kidney and bone marrow function). These tests can be helpful in determining whether patients could tolerate major surgery.

Biopsy

A person’s medical history, physical exam, and imaging test results can strongly suggest the presence of pancreatic cancer, but usually the only way to be sure is to remove a small sample of the tumor and look at it under a microscope. This procedure is known as a biopsy . Biopsies can be done in different ways.

Percutaneous (through the skin) biopsy: The doctor inserts a thin, hollow needle through the skin of the abdomen and into the pancreas to remove a small piece of the tumor. This is known as a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy. The doctor guides the needle using images from an ultrasound or CT scan.

Endoscopic biopsy: Doctors can also biopsy a tumor during an endoscopy. The doctor passes an endoscope (a thin, flexible tube with a small video camera on the end) down your throat and into the small intestine near the pancreas. At that time, the doctor may use endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) to pass a needle to the tumor or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to place a brush and remove cells from the bile or pancreatic ducts.

Surgical biopsy: Surgical biopsies are now performed less frequently than in the past. They may be helpful if the surgeon is concerned that the cancer has spread outside the pancreas and wants to examine (and possibly biopsie) other organs in the abdomen. The most common way to perform a surgical biopsy is through laparoscopy (sometimes called minimally invasive surgery). The surgeon can look at the pancreas and other organs for tumors and take biopsy samples of abnormal areas.

Some people may not need a biopsy

Rarely, the doctor may not do a biopsy on someone with a pancreatic tumor if imaging tests show that the tumor is very likely to be cancer and if it seems likely that surgery can be done to remove all of the tumor. Cancer. Instead, the doctor will proceed directly to surgery, during which the tumor cells may be examined in the laboratory to confirm the diagnosis. During surgery, if the doctor finds that the cancer has spread too far to be completely removed, only a sample of the cancer may be obtained to confirm the diagnosis, and the rest of the planned operation will be put on hold.

If treatment (such as chemotherapy or radiation) was planned before surgery, a biopsy is needed first to confirm the diagnosis.

Laboratory tests for biopsy samples

The samples obtained during the biopsy (or during surgery) are sent to a lab where they will be looked at under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells.

If cancer is found, additional tests may be done. For example, tests may be done to see if the cancer has changes (mutations) in certain genes, such as the BRCA ( BRCA1 or BRCA2 ) or NTRK genes . This could affect whether certain targeted drugs might be useful as part of your treatment.

To learn more about the different types of biopsies, how biopsy samples are tested in the laboratory, and what the results will indicate, see Testing Biopsy and Cytology Specimens for Cancer.

Genetic counseling and testing

If you’ve been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, your doctor might suggest that you see a genetic counselor to determine if you might benefit from genetic testing.

Some people with pancreatic cancer have mutations (such as those in the BRCA genes ) in every cell in their body, making them more at risk for pancreatic cancer, among other possible cancers. Undergoing these genetic tests for mutations can sometimes affect which treatments might be helpful. It may also affect whether other family members should also consider genetic counseling and testing.

How is pancreatic cancer treated?

Pancreatic cancer is usually treated with a combination of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. The type of treatment depends on the stage of the cancer or how much it has spread. Your doctor will help you evaluate treatment options based on your age, general health, and personal preferences.

Surgery:

Pancreatic cancer patients usually have some type of surgery as part of their treatment plan. The pancreas is divided into three parts: the head, the body, and the tail. The location of the tumor within the pancreas and whether the tumor has affected blood vessels and other organs near the pancreas will determine the type of surgery that is performed.

• Whipple procedure: This surgery is performed on tumors located in the head of the pancreas. During this surgery, the head of the pancreas is removed as well as the first part of the small intestine (also known as the duodenum), the gallbladder, and part of the bile duct. Sometimes parts of the stomach and nearby lymph nodes are also removed. The remaining parts of the pancreas, stomach, and intestine are reconnected so you can digest food.

• Distal pancreatectomy: This surgery is performed on tumors that are located in the body or tail of the pancreas. During this surgery, the body and tail are removed. Usually the glass is also removed.

• Total pancreatectomy: This surgery is performed on tumors located in any of the three parts of the pancreas. During this surgery, the entire pancreas is removed as well as the gallbladder, spleen, nearby lymph nodes, and part of the stomach, small intestine, and bile duct. It is possible to live without a pancreas but patients will need insulin treatment and enzyme replacement for the rest of their lives.

Sometimes patients may have tumors that are blocking the gallbladder or stomach, and surgery may be done to bypass the blockages. Although these surgeries do not remove the cancerous tumor, they can greatly improve the patient’s quality of life.

Radiotherapy:

Radiation therapy uses high-energy x-rays or other forms of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep tumors from growing. Some patients undergo radiation therapy to shrink the tumors before surgery. Three types of radiation are commonly used to treat pancreatic cancers: external beam therapy (EBT), stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT), and proton therapy. Radiation therapies are generally used in combination with surgery and/or chemotherapy.

• External beam radiation therapy (EBT): During EBT, high-energy X-rays or electron beams are applied to the tumor. The beams are usually generated by a linear accelerator and aimed at destroying cancer cells while avoiding damage to nearby normal tissues. Most patients with pancreatic cancer receive a type of external beam therapy called intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). IMRT is a form of 3-D radiation that uses linear accelerators to safely and painlessly deliver a precise dose of radiation to a tumor while minimizing the dose to surrounding normal tissue. EBT generally requires daily treatment for three to six weeks.

• Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT): SBRT is a new type of radiation therapy that uses special equipment to precisely deliver radiation with fewer high-dose treatments than traditional EBT. The total dose of radiation is divided into small “split” doses, given over several days instead of several weeks. This helps preserve healthy tissue. SBRT is used for pancreatic cancer only in specialized cancer centers.

• Proton beam radiation therapy: Proton beam radiation therapy delivers radiation to the tumor in a much more confined fashion than conventional radiation therapy. This allows the radiation oncologist to deliver a higher dose to the tumor, still minimizing side effects. This can be especially helpful in treating pancreatic cancer, since the pancreas is located in close proximity to other essential organs. Proton beam radiation therapy still requires daily treatment for four to five weeks and is only available at specialized cancer centers.

Chemotherapy

This treatment involves the use of drugs given intravenously (through the veins) or by mouth to kill cancer cells or keep them from dividing and multiplying. Chemotherapy can be used alone or in combination with radiation. Like radiation therapy, chemotherapy can help reduce symptoms and increase survival rates in patients with tumors that have spread (metastasized). Patients generally receive chemotherapy treatment sessions over a set period of time, with intervals between treatments to reduce possible side effects such as abnormal red blood cell counts, fatigue, diarrhea, mouth sores, and a compromised immune system.

New and more advanced chemotherapy options have recently been developed. These new options help prevent damage to normal, healthy tissue, while stopping cancer cells from spreading.