A slipped disc (herniated disc) most commonly occurs in people between the ages of 30 and 50. Often it causes no complaints. In some cases, however, it triggers severe back pain, sensory disturbances and even paralysis – then quick action is important. Read everything about what’s slipped disc?, symptoms, examinations and therapy of the slipped disc here!

ICD codes for herniated disc: G55 | M50 | M51

Quick overview

• Symptoms: Depending on the level and extent of the incident, eg back pain that radiates into a leg or an arm, sensory disturbances (pins and needles, tingling, numbness) or paralysis in the affected leg or arm, bladder and bowel emptying disorders

• Causes and risk factors: Usually wear and tear due to age and stress, as well as lack of exercise and overweight; more rarely injuries, congenital deformities of the spine or congenital weakness of the connective tissue.

• Treatment: Conservative measures (such as light to moderate exercise, sports, relaxation exercises, heat applications, medication) or surgery.

• Diagnosis: physical and neurological examination, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), electromyography (EMG), electroneurography (ENG), laboratory tests.

• Course and prognosis: symptoms usually disappear on their own or with the help of conservative therapy; The operation is not always successful, and complications and relapses are possible.

What’s slipped disc?

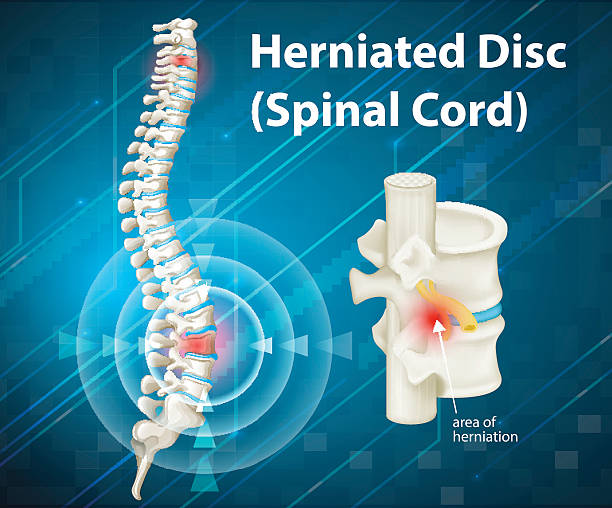

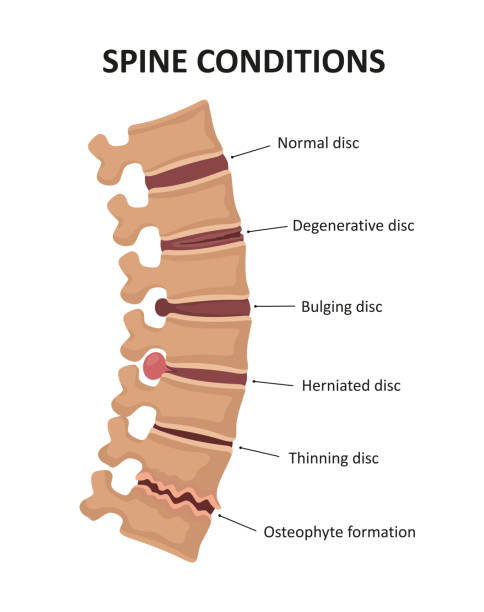

A slipped (herniated) disc is a condition of the spine in which the soft core (nucleus pulposus) protrudes from the disc, which is located between two adjacent vertebrae. It usually lies inside a tight ring of fibers (anulus fibrosus) that is damaged or unstable when a disc is slipped. As a result, the nucleus bulges out of the intervertebral disc or even penetrates the ring.

If detached parts of the gelatinous core slip into the spinal canal, the diagnosis is “sequestered slipped disc”. If the nucleus protrudes from the intervertebral disc, this often results in the nerves emerging between the vertebrae (spinal nerves) or the spinal cord in the spinal canal being compressed. Pain and dysfunction of the spinal cord occur.

The intervertebral disc bulge (disc protrusion) is to be distinguished from the slipped disc (herniated disc). Here the inner intervertebral disc tissue shifts outwards without tearing the fibrous ring of the intervertebral disc. Nevertheless, symptoms such as pain and sensory disturbances may occur. A well-known example is lumbago: This means acute shooting, severe pain in the lumbar region.

How do you recognize a slipped disc?

A slipped disc is primarily recognized by pain and neurological symptoms. For some patients, a slipped disc causes symptoms such as burning pain, tingling or pins and needles in the arms or legs, numbness or even paralysis in the extremities.

Not every slipped disc triggers the typical symptoms such as pain or paralysis. It is then often only discovered by accident during an investigation.

Symptoms of pressure on nerve roots

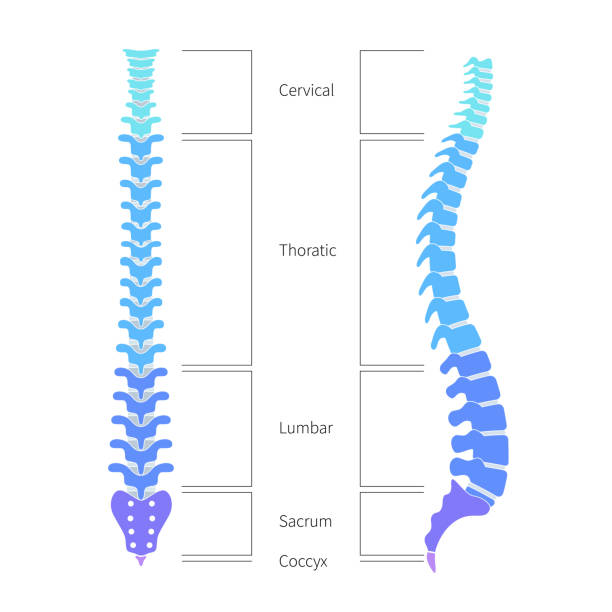

The signs of a slipped disc when pressure is applied to a nerve root depend on the level of the spine at which the affected nerve root is located – in the cervical, thoracic or lumbar spine.

Slipped disc in the cervical spine:

Occasionally, a slipped disc occurs in the cervical vertebrae (cervical disc slipped or herniated cervical spine). It primarily affects the intervertebral disc between the fifth and sixth or the sixth and seventh cervical vertebrae. Doctors use the abbreviations HWK 5/6 or HWK 6/7 for this.

Symptoms of a slipped disc in the cervical vertebrae include pain radiating into the arm. Abnormal sensations (paraesthesia) and symptoms (muscle paralysis) in the area where the affected nerve roots spread are also possible signs.

Slipped disc in the thoracic spine:

A slipped disc in the thoracic spine is very rare and in most cases affects the eighth to twelfth thoracic vertebra (Th8 to Th12). However, a slipped disc is also possible in the other thoracic vertebrae up to the first lumbar vertebra (Th13 to L1). The diagnosis is “slipped thoracic disc” (or in short: herniated thoracic disc).

Symptoms include back pain, for example, which is usually limited to the affected section of the spine. In particular, when pressure is applied to the respective nerve roots, the pain radiates into the supply area of the compressed nerve.

Slipped disc in the lumbar spine:

Symptoms of a slipped disc almost always start in the lumbar spine because the body weight exerts particularly strong pressure on the vertebrae and intervertebral discs here. Doctors speak of a lumbar disc herniation or “herniated disc LWS”. Symptoms usually arise from disc herniations between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4/L5) or between the fifth lumbar vertebra and the first coccygeal vertebra (L5/S1).

The pressure on nerve roots in the lumbar spine triggers sometimes severe pain in the lower back area, which sometimes radiates into the leg (along the supply area of the affected nerve root). Neurological deficits such as sensory disturbances (e.g. the feeling of pins and needles, tingling, numbness) and paralysis in this area are also possible.

It is particularly uncomfortable when the sciatic nerve is affected by the lumbar slipped disc. This is the thickest nerve in the body. It consists of the fourth and fifth nerve roots of the lumbar spine and the first two nerve roots of the sacrum.

The pain that occurs when the sciatic nerve is pinched is often described by patients as shooting or electrifying. They run from the buttocks over the back of the thigh down into the foot. The symptoms often worsen when you cough, sneeze or move. Doctors refer to this symptom as sciatica.

Symptoms of pressure on the spinal cord

The spinal cord extends from the posterior end of the brainstem—anatomically, this is the lowest part of the brain—to the first or second lumbar vertebra. If an intervertebral disc presses on the spinal cord, intense pain in a leg or arm and sensory disturbances (pins and needles, tingling, numbness) often occur, as when the nerve roots are squeezed. Increasing weakness in both arms and/or legs are also possible consequences of a slipped (herniated) disc.

Other signs that the intervertebral disc is pressing directly on the spinal cord include dysfunction of the sphincter muscles of the bladder and bowel. They are accompanied by numbness in the anal and genital areas and are considered an emergency – the patient must be hospitalized immediately!

Symptoms of pressure on the horse’s tail

The spinal cord continues at the lower end in the lumbar region in a nerve fiber bundle, the horse’s tail (cauda equina). It extends to the sacrum. This is the part of the spine that connects the two pelvic bones.

Pressure against the horse’s tail (cauda syndrome) may result in problems with urination and bowel movements. In addition, those affected no longer have any feeling in the area of the anus and genitals or on the inside of the thighs. Sometimes the legs are paralyzed. Patients with such symptoms should also go to the hospital immediately.

Suspected slipped disc symptoms

A slipped (Herniated) disc does not always trigger symptoms such as back pain – even if the X-ray shows a prolapse. Sometimes tension, changes in the spine (e.g. due to wear and tear, inflammation) or neurological diseases are the cause of alleged slipped disc symptoms. Pain in the leg is also not a clear sign – a herniated disc with pressure on a nerve root is just one of several possible explanations. Sometimes there is a blockage in the joint between the sacrum and the pelvis (sacroiliac joint blockage). In most cases, leg pain associated with back problems cannot be attributed to a nerve root.

What are causes and risk factors?

The cause of a slipped disc is usually age-related and stress-related wear and tear (degeneration) of the connective tissue ring of the intervertebral disc: it loses its stabilizing function and tears under heavy loads. The gelatinous core partially emerges and presses on a nerve root or the spinal cord.

The compressed nerves in the spinal cord (spinal nerves) are severely irritated and increasingly transmit pain signals to the brain. In the event of a massive bruise, the transmission of stimuli may be so badly disrupted that symptoms of paralysis occur.

The frequency of slipped discs decreases again from the age of 50 because the core of the disc loses fluid with advancing age and therefore leaks less frequently.

In addition, lack of exercise and obesity are important risk factors for slipped discs. Typically, the abdominal and back muscles are then also weak. Such instability of the body promotes incorrect loading of the intervertebral discs, since only strong trunk muscles relieve the spine.

Other possible triggers of a slipped disc are incorrect posture, jerky movements and sports in which the spine is shaken (horseback riding, mountain biking) or twisted (tennis, squash). The same goes for heavy physical work like lifting heavy loads. However, this alone does not cause a slipped disc. This only happens when a disc is already showing signs of wear.

Injuries (such as those caused by falling down stairs or a traffic accident) and congenital misalignments of the spine are less common as the cause of a slipped disc.

In some cases, a genetically determined weakness of the connective tissue, stress and an unbalanced or incorrect diet favor the development of a slipped disc.

What helps with a slipped disc?

Most patients are primarily interested in what helps with a slipped disc. The answer to this mainly depends on the symptoms. In more than 90 percent of patients, conservative treatment of a herniated disc is sufficient, i.e. therapy without surgery. This is especially true if the slipped disc is causing pain or mild muscle weakness but no other/more serious symptoms.

The more serious symptoms include paralysis and disorders of the bladder or rectum function. In such cases, surgery is usually performed. Surgery may also be considered if symptoms persist despite conservative treatment for at least three months.

Treatment without surgery

As part of the conservative treatment of a slipped disc, the doctor today only rarely recommends immobilization or bed rest. In the case of a herniated cervical disc, however, it may be necessary to immobilize the cervical spine with a neck brace. In the case of severe pain due to a slipped disc in the lumbar spine, a step bed position is sometimes helpful for a short time.

In most cases, conservative herniated disc therapy involves mild to moderate exercise. Normal everyday activities are – as far as the pain allows – definitely recommended. Many patients receive physiotherapy as part of outpatient or inpatient rehabilitation. The therapist practices low-pain movement patterns with the patient, for example, and gives tips for everyday activities.

Regular exercise is also very important in the long term if you have a slipped disc: On the one hand, the change between loading and relieving the intervertebral discs promotes their nutrition. On the other hand, physical activity strengthens the trunk muscles, which relieves the intervertebral discs. Therefore, exercises to strengthen the back and abdominal muscles are highly recommended in the case of a slipped disc. Physiotherapists show patients these exercises as part of a back school. The patients should then train regularly themselves.

In addition, you can and should do sport with a herniated disc, provided it is disc-friendly. Examples include aerobics, running, backstroke, cross-country skiing and dancing. Tennis, downhill skiing, soccer, handball and volleyball, golf, ice hockey, judo, karate, gymnastics, canoeing, bowling, wrestling, rowing and squash are less good for the intervertebral discs.

If you don’t want to do without a sport that damages your intervertebral discs, you should do exercise and strength training to compensate, for example by running, cycling or swimming regularly. If unsure, patients should discuss the type and extent of sporting activities with their doctor or physiotherapist.

Many people with back pain from a slipped disc (or other reasons) benefit from relaxation exercises. These help, for example, to relieve pain-related muscle tension.

Heat applications have the same effect. Therefore, they are also often part of the conservative treatment of slipped discs.

Medicines are used if necessary. These include, above all, painkillers such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen, diclofenac et cetera). In addition to a pain-relieving effect, they also have an anti-inflammatory and decongestant effect. Other active ingredients may also be used, such as COX-2 inhibitors (cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors) and cortisone. They also have anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving effects. If the pain is very severe, the doctor will prescribe opiates for a short time.

Pain therapy for slipped discs is closely monitored by the doctor to avoid serious side effects. It is best for patients to follow the doctor’s instructions when using painkillers.

In some cases, the doctor will prescribe muscle-relaxing drugs (muscle relaxants) because the muscles become tense and hardened due to the pain and a possible relieving posture. Sometimes antidepressants are useful, for example in the case of severe or chronic pain.

When is an operation necessary?

Doctor and patient decide together whether a slipped disc operation is to be performed. The criteria for a disc operation are:

• Symptoms indicating pressure against the spinal cord (surgery soon or immediately).

• Severe paralysis or increasing paralysis (immediate surgery).

• Symptoms indicating pressure against the horse’s tail (cauda equina) (immediate surgery).

• Less pain and increasing paralysis (quick surgery because there is a risk that the nerve roots are already dying).

There are different techniques for the surgical treatment of a slipped disc. Microsurgical procedures are standard today. They reduce the risk of scarring. Alternatively, minimally invasive procedures can be considered in certain cases for a slipped disc operation.

Operation: microsurgical discectomy

The most widespread technique in the surgical treatment of a slipped disc is microsurgical discectomy (discus = intervertebral disc, ectomy = removal). The affected intervertebral disc is removed with the help of a surgical microscope and the smallest special instruments. This is intended to relieve the spinal cord nerves (spinal nerves) that are constricted by the herniated disc and are causing symptoms.

Only small skin incisions are required to insert the surgical instruments. Therefore, the microsurgical surgical technique is one of the minimally invasive procedures.

All slipped discs can be removed by microsurgical discectomy – regardless of the direction in which the part of the disc has slipped. In addition, the surgeon can see directly whether the strained spinal nerve has been relieved of any pressure.

Procedure of the discectomy

Microsurgical discectomy is performed under general anesthesia. The patient is in a kneeling position with the upper body at a higher level on the operating table. This increases the distance between the vertebral arches and makes it easier to open the spinal canal.

First, the surgeon makes a small skin incision over the diseased area of the disc. Then he carefully pushes the back muscles to the side and partially cuts (as little as necessary) the yellowish band (ligamentum flavum) that connects the vertebral bodies. This allows the surgeon to look directly into the spinal canal with the microscope. Sometimes he has to remove a small piece of bone from the vertebral arch to improve vision.

Using special instruments, he now loosens the prolapsed disc tissue under visual control of the spinal nerve and removes it with a grasping forceps. Larger defects in the fibrous ring of the intervertebral disc can be sutured microsurgically. Parts of the intervertebral disc (sequestrum) that have slipped into the spinal canal are also removed in this way. In the last step of the disc surgery, the surgeon closes the skin with a few sutures.

Possible complications

During microsurgical intervertebral disc surgery, it is possible that the nerve that is to be relieved is injured. Possible consequences are sensory and movement disorders in the legs, functional disorders of the bladder and intestines and sexual disorders. However, such complications are rare.

As with any operation, there is a certain risk of anesthesia with this intervertebral disc operation as well as the risk of infections, wound healing disorders and post-operative bleeding.

Some of the patients feel leg pain or tingling again after weeks or months, even after optimal disc surgery and prolapse removal. This late consequence is called “failed back surgery syndrome”.

Course of the operation

The open discectomy is essentially the same as the microsurgical slipped disc operation, but larger incisions are made and the surgical area is not assessed with a micro-optic, but from the outside.

Possible complications

The potential complications of open discectomy are comparable to those of microsurgical discectomy, but occur more frequently.

After the operation

Sometimes the bladder has to be emptied with a catheter on the first day after open disc surgery. Bladder and bowel function return to normal within a very short time.

The patient is usually allowed to get up again in the evening of the day of the operation. The next day he usually starts with physiotherapy exercises to strengthen the muscles and ligaments of the back again. The patient usually stays in the hospital for only a few days.

Surgery: Endoscopic discectomy

The minimally invasive techniques of an intervertebral disc operation include microsurgical methods as well as so-called percutaneous endoscopic methods. The intervertebral disc is removed with the help of endoscopes, video systems and micro-instruments (partly motor-driven), which are inserted through small skin incisions. The patient is usually semi-conscious and under local anesthesia. This enables him to communicate with the operator.

Endoscopic herniated disc surgery is not feasible for every patient. It is unsuitable, for example, if parts of the intervertebral disc have become detached (sequestered herniated disc) and have slipped up or down in the spinal canal. Endoscopic discectomy is also not always applicable in the case of slipped discs in the transition area between the lumbar spine and the sacrum. Because here the iliac crest blocks the way for the instruments.

By the way: Endoscopic methods can not only remove the entire intervertebral disc (discectomy), but also only parts of the gelatinous core (nucleus). Then doctors speak of percutaneous endoscopic nucleotomy.

Course of the operation

The patient lies prone during endoscopic disc surgery. The skin over the affected section of the spine is disinfected and locally anesthetized.

One or two small metal tubes are advanced into the intervertebral disc space via one or two small incisions under X-ray control. These are working sleeves with a diameter of three to eight millimeters. They allow instruments such as small grasping forceps and an endoscope to be inserted into the disc space. The latter has special lighting and optics. The images from the operation area inside the body are projected onto a video monitor where the operating doctor sees them.

The surgeon now selectively removes disc tissue that is pressing on a nerve. After the endoscopic disc operation, he sews up the incisions with one or two stitches or supplies them with special plasters.

Possible complications

The complication rate in endoscopic disc surgery is relatively low. Nevertheless, there is a certain risk of injuring nerves. Possible consequences are sensory and movement disorders in the legs as well as functional disorders of the bladder and intestines.

As with any operation, there is also a risk of infections, wound healing disorders and postoperative bleeding.

Compared to microsurgical discectomy, the recurrence rate (recurrence rate) is higher for endoscopic disc surgery.

After the operation

If the endoscopic disc surgery is uncomplicated, the patient is able to get up within three hours and leave the hospital the same day or the next morning. Physiotherapy exercises are usually started the day after the operation.

Intervertebral disc surgery with an intact fibrous ring

If someone has just a mild slipped disc where the fibrous ring is still intact, there is sometimes an opportunity to use a minimally invasive procedure to reduce or shrink the affected disc in the area of the nucleus. This relieves the pressure on nerve roots or spinal cord. This technique can also be used for bulging discs (here the fibrous ring is always intact).

The advantage of minimally invasive procedures is that they only require small skin incisions, are less risky than open surgery and are usually performed on an outpatient basis. However, they are only an option for a small number of patients.

Course of the operation

In this minimally invasive disc surgery, the skin over the affected section of the spine is first disinfected and locally anesthetized. Sometimes the patient is put into a twilight sleep. Now the doctor carefully sticks a hollow needle (cannula) into the middle of the affected intervertebral disc under image control. He inserts working instruments through the hollow canal to reduce or shrink the tissue of the gelatinous core:

To do this, he uses a laser, for example, which uses individual flashes of light to vaporize the gelatinous core inside the intervertebral disc (laser disc decompression). The gelatinous core consists of more than 90 percent water. By vaporizing tissue, the volume of the core is reduced. In addition, the heat destroys “pain receptors” (nociceptors).

In the thermal lesion, the surgeon advances a thermal catheter under X-ray control to the inside of the intervertebral disc. The catheter is heated up to 90 degrees Celsius, so that part of the intervertebral disc tissue is boiled away. At the same time, the outer fiber ring should solidify through the heat. Some of the pain-conducting nerves are also destroyed.

In what is called nucleoplasty, the doctor uses radio frequencies to generate heat and vaporize the tissue.

Alternatively, the doctor inserts a decompressor through the cannula into the inside of the disc. At the top is a rapidly rotating spiral thread. It cuts into the tissue and at the same time sucks out up to a gram of the gelatinous mass.

During chemonucleolysis, the enzyme chymopapain is injected, which chemically liquefies the gelatinous core inside the intervertebral disc. After a certain waiting time, the liquefied core mass is sucked out through the cannula. It is very important here that the fibrous ring of the intervertebral disc in question is completely intact. Otherwise there is a risk that aggressive enzyme will escape and cause serious damage to the surrounding tissue (such as nerve tissue).

Possible complications

One of the possible complications of minimally invasive disc surgery is bacterial disc inflammation (spondylodiscitis). Under certain circumstances, it spreads to the entire vertebral body. Therefore, the patient is usually given an antibiotic as a preventive measure.

After the operation

In the first few weeks after minimally invasive disc surgery, the patient should rest physically. Sometimes the patient is prescribed a corset (elastic bodice) for relief during this period.

Surgery: implants

As part of the surgical treatment of a slipped disc, the worn disc is sometimes replaced with a prosthesis to preserve the mobility of the spine. The intervertebral disc implant is intended to maintain the space between the vertebrae and their normal mobility and to relieve pain.

So far it is unclear which patients will benefit from an intervertebral disc implant and what the long-term successes will look like. Ongoing studies have yielded quite positive results so far. However, there are still no real long-term results, especially since most patients are middle-aged at the time of the disc operation, i.e. usually still have some life ahead of them.

Nucleus pulposus replacement

In the early stages of intervertebral disc wear (intervertebral disc degeneration), it is possible to replace or support the gelatinous core of the intervertebral disc (nucleus pulposus). Doctors usually use hydrogel cushions as a kind of artificial gelatinous core. This gel comes very close to the biochemical and mechanical properties of the natural gelatinous core because it is able to absorb liquid. Like the intervertebral disc, it absorbs water when it is relieved and releases it again when it is loaded.

Depending on the extent of the finding and depending on the procedure, local anesthesia or short anesthesia is often sufficient for this disc operation. The hydrogel is usually inserted using a hollow needle (under X-ray vision). Those affected are often able to get up on the same day and move freely the following day. The process is being further developed and monitored in clinical studies worldwide. Little is known about long-term results.

Total disc replacement

In a total disc replacement, the doctor removes the disc and portions of the base and end plates of the adjacent vertebrae. In most models, the intervertebral disc replacement consists of titanium-coated base and cover plates and a polyethylene inlay (similar to common hip prostheses).

About the course of the intervertebral disc operation: The old intervertebral disc is removed; in addition, part of the cartilage on the base and end plates of the adjacent vertebrae is rasped away. X-rays can be used to determine the size of the intervertebral disc and select a suitable implant. Depending on the model, the surgeon then chisels a small, vertical slit into the base and cover plates of the adjacent vertebrae. It serves to anchor the prosthesis. Then the surgeon inserts the disc replacement. The pressure of the spine stabilizes the implant. Bone material grows into the specially coated base and cover plates of the full intervertebral disc prosthesis within three to six months.

The patient is able to get up on the first day after the operation. In the first few weeks, he must not lift heavy loads and must avoid extreme movements. An elastic corset, which the patient puts on himself, is used for stabilization.

A total disc replacement is not suitable for patients who suffer from osteoporosis (bone loss) or for whom the vertebra to be treated is unstable.

Investigations and diagnosis

If your back pain is unclear, first consult your family doctor. If a slipped disc is suspected, he will refer you to a specialist, such as a neurologist, neurosurgeon or orthopaedist.

In order to determine a slipped disc, the patient is usually questioned (anamnesis) and a thorough physical and neurological examination is carried out. Imaging procedures such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are only necessary in certain cases.

Doctor-patient conversation

In order to clarify the suspicion of a slipped disc, the doctor first collects his medical history (anamnesis) in conversation with the patient. For example, he asks:

• What complaints do you have? Where exactly are they performing?

• How long have the symptoms existed and what triggered them?

• Does the pain get worse when you cough, sneeze, or move?

• Do you have trouble urinating or having a bowel movement?

The information helps the doctor to pinpoint the cause of the symptoms more closely and to estimate where in the spine they may be originating.

Physical and neurological examination

The next step is physical and neurological examinations. The doctor carries out palpation, percussion and pressure tests in the area of the spine and back muscles in order to discover abnormalities or pain points. It also tests the range of motion of the spine. Muscle strength, feeling in the affected arms or legs and reflexes are also tested. The type and localization of the symptoms often give the doctor an indication of the level of the spine where a slipped disc is present.

Imaging procedures

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) make a herniated disc visible. The doctor then recognizes, for example, the extent of the prolapse and the direction in which it occurred: In most cases, there is a mediolateral disc herniation. The gelatinous core that has escaped has slipped between the intervertebral foramina and the spinal cord canal.

A lateral herniated disc can be recognized by the fact that the gelatinous core has slipped sideways and leaks into the intervertebral foramina. If he presses on the nerve root of the affected side, unilateral complaints result.

A medial disc herniation is less common is less common : the jelly-like mass of the core of the intervertebral disc emerges in the middle toward the back in the direction of the spinal canal (spinal cord canal) and may press directly on the spinal cord.

When are imaging procedures necessary for a slipped disc?

A CT or MRI is only necessary if the doctor’s discussion or physical examination have revealed a clinically significant slipped disc. This is the case, for example, if paralysis occurs in one or both legs, the bladder or bowel function is disturbed, or severe symptoms persist for weeks despite treatment. MRI is usually the first choice.

Imaging is also needed when back pain is accompanied by symptoms suggestive of a possible tumor (fever, night sweats, or weight loss). In these rare cases, the space between the spinal cord and the spinal cord sac (dural space) needs to be visualized using an X-ray contrast medium (myelography or myelo-CT).

A normal X-ray examination is usually not useful if a slipped disc is suspected, as it only shows bones and not soft tissue structures such as intervertebral discs and nerve tissue.

Imaging procedures are not always helpful

Even if a slipped disc is discovered in the MRI or CT, this does not have to be the cause of the symptoms that prompted the patient to see the doctor. In many cases, a slipped disc runs its course without symptoms (asymptomatic).

In addition, imaging procedures sometimes contribute to the patient’s pain becoming chronic. Because looking at a picture of your own backbone apparently has a negative psychological effect in some cases, as studies show. Especially in the case of diffuse back pain without neurological symptoms (such as sensory disturbances or paralysis), it is therefore advisable to wait and see. An imaging examination is only indicated if the symptoms do not improve after six to eight weeks.

Measurement of muscle and nerve activity

If paralysis or sensory disturbances occur in the arms or legs and it is unclear whether this is the direct result of a slipped disc, electromyography (EMG) or electroneurography (ENG) may provide certainty. With the EMG, the doctor treating you measures the electrical activity of individual muscles using a needle. In cases of doubt, ENG reveals which nerve roots are being squeezed by the slipped disc or whether another nerve disease is present, such as polyneuropathy.

Laboratory tests

In rare cases, certain infectious diseases such as Lyme disease or herpes zoster (shingles) cause symptoms similar to a slipped disc. If the imaging shows no findings, the doctor has the option of taking a blood sample and possibly a sample of the cerebrospinal fluid (Liquor cerebrospinalis) from the patient. These samples are examined in the laboratory for infectious agents such as Borrelia or herpes zoster viruses.

If necessary, the doctor arranges for the determination of general parameters in the blood. These include inflammatory values such as the number of leukocytes and the C-reactive protein (CRP). These are important, for example, if the symptoms may be due to inflammation of the intervertebral disc and adjacent vertebral bodies (spondylodiscitis).

Herniated cervical disc

The age-related wear and tear of vertebral joints and intervertebral discs is the main reason why the cervical spine often has a herniated disc, especially in older people: the vertebral joints loosen and change over the years, the intervertebral discs wear down increasingly.

The effects of a slipped disc in the cervical spine usually affect the shoulders, arms and chest area, because the supplying nerves leave the spinal cord at this level.

When younger people suffer a herniated cervical disc, the cause is often an injury or an accident. For example, an abrupt turning movement of the head sometimes causes a disc between the cervical vertebrae to prolapse.

Course of the disease and prognosis

In about 90 out of 100 patients, the pain and restricted movement caused by an acute herniated disc subside on its own within six weeks. The displaced or protruding disc tissue is likely to be removed by the body or displaced so that the pressure on the nerves or spinal cord is relieved.

If treatment is necessary, conservative measures are usually sufficient. They are therefore often the treatment of choice for a herniated disc. The duration of regeneration and the chances of recovery depend on the severity of the slipped disc.

Even after successful treatment, there is a possibility that a new herniation will occur in the same disc or between other vertebral bodies. It is therefore advisable to train the trunk muscles regularly after surviving a slipped disc and to heed other tips that can be used to prevent a herniated disc.

After an operation

Surgery for a slipped (herniated) disc should be carefully considered. It is often successful, but there are always patients for whom the procedure does not bring the desired freedom from pain in the long term.

Doctors then speak of failed back surgery syndrome or postdiskectomy syndrome. It arises because the intervention did not eliminate the actual cause of the pain or created new causes of pain. These include, for example, inflammation and scarring in the surgical area.

Another possible complication of an intervertebral disc operation is damage to nerves and vessels during the procedure.

If a patient feels worse than before after a disc operation, there are various possible reasons for this. In addition, follow-up operations are sometimes necessary. This is also the case when patients who have been operated on later experience renewed herniated discs.

A slipped disc should therefore only be operated on if it is urgently needed, for example because it is causing paralysis. In addition, the expected benefits should be significantly greater than the risks. In order to improve the results, many patients stay in rehabilitation clinics after the operation.

So far there is no way to find out in advance which patients with a slipped disc will benefit the most from disc surgery.

Can a slipped disc be prevented?

A healthy, strong trunk musculature is the prerequisite for the body to master everyday challenges. Preventive measures include:

• Pay attention to your body weight: Being overweight puts strain on your back and encourages a slipped disc.

• Do sports regularly: Hiking, jogging, cross-country skiing, crawl and backstroke, dancing, water aerobics and other types of gymnastics that strengthen the back muscles are particularly good for the back.

• Certain relaxation techniques, such as yoga, tai chi, and Pilates, also promote good posture and help strengthen your core and back.

• If possible, sit up straight and in a chair of normal height. Change your sitting position frequently. An accompanying strength training stabilizes the core muscles.

• Position objects that you use often at an easily accessible height: this relieves strain on your eyes and arms and prevents you from overloading your cervical spine. This is also important for a back-friendly workplace.

• Avoid deep and soft seating; a wedge-shaped seat cushion is recommended.

• Working while standing: The workplace must be high enough for you to (permanently) be able to stand upright.

• Never lift very heavy objects with your legs straight and your spine bent: instead, bend your knees, keep your spine straight and lift the load “out of your legs”.

• Distribute the load in both hands so that the load on the spine is evenly distributed.

• Do not bend your spine to the opposite side when carrying a load.

• When carrying loads, keep your arms close to your body: Do not shift your body weight backwards and avoid arching your back.

• Make sure that your spine does not buckle when you sleep. It makes sense to have a good mattress (the hardness should correspond to the body weight) plus a slatted frame and possibly a small pillow to support the natural shape of the spine.

This advice is particularly aimed at people who have already had a herniated disc (slipped disc).